Thinning indicates a profound impact of humans and could affect satellites and GPS

Humanity’s enormous emissions of greenhouse gases are shrinking the stratosphere, a new study has revealed.

The thickness of the atmospheric layer has contracted by 400 metres since the 1980s, the researchers found and will thin by about another kilometre by 2080 without major cuts in emissions. The changes have the potential to affect satellite operations, the GPS navigation system and radio communications.

The discovery is the latest to show the profound impact of humans on the planet. In April, scientists showed that the climate crisis had shifted the Earth’s axis as the massive melting of glaciers redistributes weight around the globe.

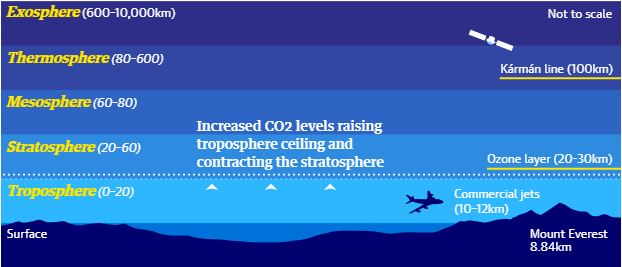

The stratosphere extends from about 20km to 60km above the Earth’s surface. Below is the troposphere, in which humans live, and here carbon dioxide heats and expands the air. This pushes up the lower boundary of the stratosphere. But, in addition, when CO2 enters the stratosphere it actually cools the air, causing it to contract.

Greenhouse gas emissions are changing the structure of Earth’s lower atmosphere

The shrinking stratosphere is a stark signal of the climate emergency and the planetary-scale influence that humanity now exerts, according to Juan Añel, at the University of Vigo, Ourense in Spain and part of the research team. “It is shocking,” he said. “This proves we are messing with the atmosphere up to 60 kilometres.”

Scientists already knew the troposphere was growing in height as carbon emissions rose and had hypothesised that the stratosphere was shrinking. But the new study is the first to demonstrate this and shows it has been contracting around the globe since at least the 1980s, when satellite data was first gathered.

The ozone layer that absorbs UV rays from the sun is in the stratosphere and researchers had thought ozone losses in recent decades could be to blame for the shrinking. Less ozone means less heating in the stratosphere. But the new research shows it is the rise of CO2 that is behind the steady contraction of the stratosphere, not ozone levels, which started to rebound after the 1989 Montreal treaty banned CFCs.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, reached its conclusions using the small set of satellite observations taken since the 1980s in combination with multiple climate models, which included the complex chemical interactions that occur in the atmosphere.

“It may affect satellite trajectories, orbital lifetimes, and retrievals […] the propagation of radio waves, and eventually the overall performance of the Global Positioning System and other space-based navigational systems,” the researchers said.

Prof Paul Williams, at the University of Reading in the UK, who was not involved in the new research, said: “This study finds the first observational evidence of stratosphere contraction and shows that the cause is in fact our greenhouse gas emissions rather than ozone.”

“Some scientists have started calling the upper atmosphere the ‘ignorosphere’ because it is so poorly studied,” he said. “This new paper will strengthen the case for better observations of this distant but critically important part of the atmosphere.”

“It is remarkable that we are still discovering new aspects of climate change after decades of research,” said Williams, whose own research has shown that the climate crisis could triple the amount of severe turbulence experienced by air travellers. “It makes me wonder what other changes our emissions are inflicting on the atmosphere that we haven’t discovered yet.”

The dominance of humanity activities on the planet has led scientists to recommend the declaration of a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene.

Among the suggested markers of the Anthropocene are the radioactive elements scattered by nuclear weapons tests in the 1950s and domestic chicken bones, thanks to the surge in poultry production after the second world war. Other scientists have suggested widespread plastic pollution as a marker of a plastic age, to follow the bronze and iron ages.

By Damian Carrington (The Guardian)