Eight Pacific countries created a revolutionary system that brings in $500m a year and prevents the overfishing that blights other regions

It has been described as “the most remarkable achievement of the Pacific island countries in the last 50 years”.

In 1982, eight, mostly minuscule Pacific island countries in whose waters much of the world’s skipjack tuna was caught got together and decided to do something to get a share of the profits, of which they received precisely nothing.

In a shining example of regional cooperation, the group, known as the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), successively outmanoeuvred the United States, Japan and Taiwan, and later mainland China and the European Union.

“It was a David versus Goliath situation from the start,” said Jonathan Pryke, director of the Pacific Islands Program of the Lowy Institute in Sydney.

Over four decades of trial and error, they created a system that Pryke calls “revolutionary” that today not only yields them half a billion dollars a year but also prevents the overfishing that international fishing fleets have carried out to deplete the waters of most poor countries.

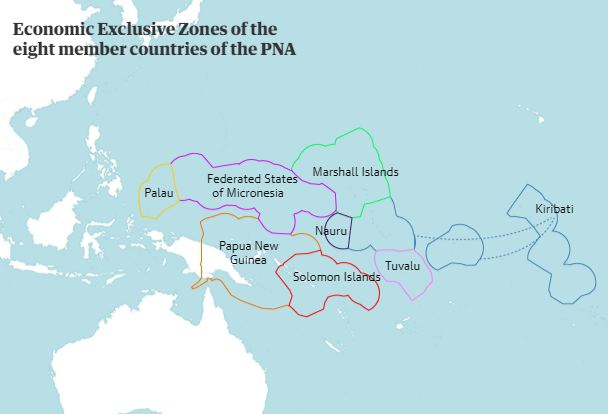

They were, from east to west, six micro-states made up mostly of tiny islands (Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Tuvalu, Nauru, the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau) and two midsized countries, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands.

The mice that roared: Photograph: Opla/Getty Images/iStockphoto

The key to success, said Ludwig Kumoru, the outgoing chief executive of the PNA, was to jettison a system in which the PNA nations undercut each other in trying to sell fishing rights in their waters to foreign fleets – and replace it with another, called the Vessel-Day Scheme. That scheme sees them calculate how much tuna fishing is sustainable and then divides that amount up into fishing days for which fishing companies bid.

“We set the minimum price of a day at US$8,000 a day, up from $2,500 at the beginning, but demand was so high that we’ve been getting $12,000 to $14,000 a day,” Kumoru said.

“All our fish stocks are healthy,” said Transform Aqorau, a Solomon Islands lawyer who became the first chief executive of the PNA in 2010, and was largely responsible for introducing the scheme.

“And they are likely are likely to remain healthy if recent levels of exploitation continue,” confirmed John Hampton, chief scientist as the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, the region’s top fisheries scientist.

‘Host countries weren’t getting a penny’

Sean Dorney, a veteran Pacific correspondent for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, remembers being present at the creation of the PNA in 1982 – a meeting on the phosphate-rich island nation of Nauru of the fisheries ministers of the 16-nation Forum Fisheries Agency, which oversees fishing in the Pacific and includes Australia and New Zealand. Dorney flew in from Port Moresby because he sensed something big was about to happen.

“There was a palpable sense of frustration,” he said. “None of the fish was being landed in any of the eight countries where they were fished, they were all trans-shipped to refrigerated ships and taken to Bangkok or Japan, and the host countries weren’t getting a penny.”

Local fishermen in Tuvalu see a familiar sight nearby. Photograph: Fiona Goodall/Getty Images for Lumix

When the eight countries signed what would become the original Nauru agreement – to coordinate their relations with the foreign fishing fleets – “They had no clear sense of what they realistically could expect,” Dorney said. “All we knew was that this was a historic moment.”

Looking back, “the creation of PNA is probably the most remarkable achievement of the Pacific island countries in the last 50 years, a shining example of cooperation,” he added.

Lowy’s Pryke said: “In today’s climate, it would be much harder to create a PNA, because regionalism is at a low ebb.”

The PNA took years to refine into a system that generated significant profit for the Pacific nations. Fees grew slowly in the decade after signing the PNA.

By the mid-1990s, the massive expansion of the international tuna fleets was beginning to peak, but the eight countries were receiving a tiny fraction of the profits realised by the fleets when the fish was landed. “So there was no real cap, no competition and no scarcity, and the fees they collected were still way below 5% of the landed value of the fish,” said Michael Lodge, a young British lawyer, joined the Forum Fisheries Agency, the regional agency that supervised Pacific fishing, as its legal adviser in 1989.

It wasn’t until 2011 that the PNA hit on the winning formula. The Vessel Day Scheme, which had already been implemented, was refined to allow the secretariat to sell days valid in all eight countries, then bill the fleet for the days fished in each country and pass on those fees to the countries.

The system also allowed the countries momentarily without fish – say the Western Pacific’s Federated States of Micronesia in an El Niño year – to sell its days to the Central Pacific’s Kiribati, where the fish were, and Kiribati could resell them to the fishers, evening out the yearly revenues of each state.

This trading enormously increased the value of each day, said Aqorau. “Now we’re getting 25% of the dockside sale price of the skipjack, up from 2% or 3% a decade ago.”

For Kiribati, which has the group’s biggest Exclusive Economic Zone (bigger than the land area of India) but one of the smallest economies (it has just 113,000 people), the scheme has raised fishing revenues from $25m a decade ago to $160m, or $1,400 per capita, allowing for all manner of social spending and infrastructure work, notably to raise the frequently flooded, overpopulated parts of Tarawa, the capital, as well as to provide government funding for students, people with disabilities, those who are unemployed, and elderly people.

“It’s hugely improved the life of the people,” said former president Teburoro Tito.

In Papua New Guinea, the largest country and economy in the Pacific Islands, the increase in fees income from $20m to $80m a year has been mostly earmarked to develop sustainable coastal fisheries and cooperative fish farming.

“It’s made a big difference in coastal communities,” added Kumoru, the PNA’s acting chief executive, who is from PNG.

By Christopher Pala